This newsletter series is sent monthly, stay up to date by subscribing here.

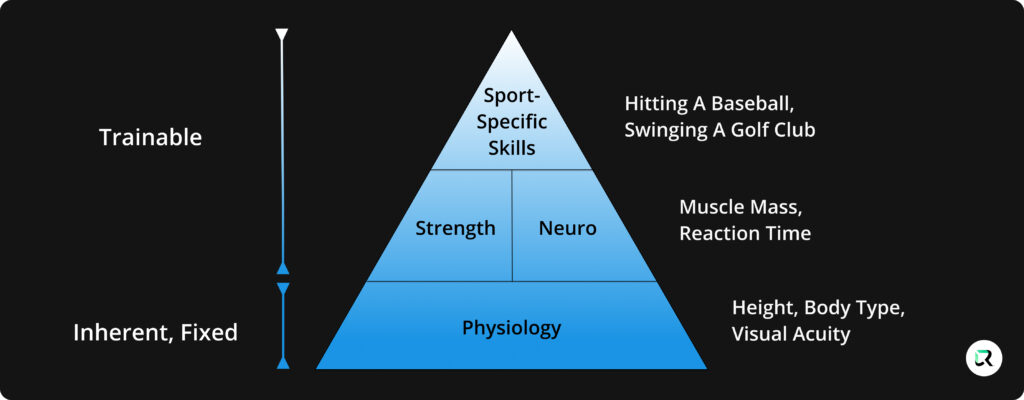

What’s a trainable skill, versus what are you born with?

If we treat human performance like a pyramid, the bottom level is inherited human physiology. This would be the foundation for any specific ability and varies from person to person.

At this bottom level, genetics plays the lead role – some people are born with larger bone structure and sharper eyes, and this can give them an advantage from an early age.

Intuitively, this makes sense. Naturally good eyes will give you an advantage as you rank up through leagues. A publication found major league MLB players to have slightly better visual acuity (20/12) than minor leaguers, and much better acuity than the general population (20/20).

As you climb the pyramid, you enter abilities that are trainable. That includes areas such as muscle mass, cardio endurance, and eye-hand coordination. They’re improved with weight training, cardio training, and neuro training, respectively. This mid-tier level is where Reflexion trains neuro skills.

Let’s Talk Real World

One step above that is sport or action specific tasks – hitting a baseball, shooting a basket, and serving a tennis ball are all examples. These are skills that have specific techniques and require practice.

For example, the best way to learn bowling is to… bowl. No surprises there.

It’s why many athletes can switch easily between sports. Shooting a basketball doesn’t make you good at volleyball, but they both require excellent eye-hand coordination. If you’re good enough at one, you can probably pick up the other relatively easily.

An Example in Baseball

So how do cognitions play into the real world?

Last December, we had Dr. Dan Laby on one of our podcast episodes. He’s a very well respected researcher in the sports vision space, and the author of the MLB visual acuity paper referenced above. Here’s what he had to say on vision training’s impact on the field.

“Having a faster reaction time doesn’t mean you’re going to swing at more pitches or swing the bat faster. What it seems to mean from the data is that it gives you the option to sit back a little bit more, to see more of the pitch…[and] to make a better decision. Is this [pitch] the ball you want to hit, or can you let it go?

And so we see people that have these faster reaction times actually allow more strikes, because they’re waiting for the right pitch. Now they don’t strike out, in fact they walk more…but if they have the count in their favor, and this pitch isn’t exactly where they want to hit it, they’ll take the strike.”

The Research Gap

Knowing where neuro training fits into this hierarchy is important for understanding how it will translate to the real world, and why there isn’t more research in this space yet.

Trying to analyze how neuro training improves on-field performance is like trying to determine how bench press translates to QB sacks for a lineman. Very few would argue bench press isn’t an important exercise, but scientifically proving and showing that sort of relationship is a challenging task.

The Takeaway

When looking at ways to improve human performance, sport-specific tasks represent only a portion of an athlete’s opportunity. Fundamental abilities related to strength, cardio, and neuro all offer ways to train.

And as the neuro training and assessment industry grows, more research will be needed to better validate its effectiveness and reliability, and we hope to be a leader in this field.

If you’re interested in seeing some of the research supporting neuro training now, including topics beyond just sports, take a look at this database we put together.

Not signed up for the newsletter? Do so here.